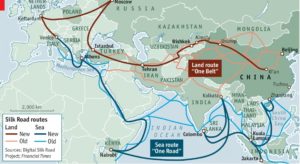

China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative will be the greatest infrastructure investment project of our time – or something along those lines. This has become the standard mantra in investing and media circles and can be heard almost as often as the deflected answer to any Bitcoin related question – “Blockchain a revolutionary technology”. We often hear that OBOR is the Marshall Plan of the 21st Century, well what if the Marshall Plan was funded by the Soviet Union? What would its chances of success have been? For us, OBOR represents one of the largest Geo-Political risks of the next decade.

In 2016 we published a piece called ‘China, the Reluctant Superpower’ which came out of a red-teaming exercise our team conducted looking at the potential responses of China to a number of theoretical threats to its geo-strategic locations around the world, including a future nationalist coup in Djibouti that leads to an expropriation of Chinese military assets and access to its Obock Port, an unchecked insurgent uprising in North East Myanmar that cuts off oil and gas flows from the Kyaukpyu pipeline, the collapse of the Pakistan government and thus a denial of access to Gwadar Port and a sustained and unchecked campaign of terrorist attacks on vessels in the Malacca Straight by Islamic extremist groups from inside a politically unstable Indonesia. The thesis was that while China may not want to wield hegemonic or imperial power in the same ways the world has historically come to expect of superpowers, there may arise certain conditions that draw China into acting in the same way nonetheless.

Xi’s reform of the Central Military Commission which significantly increased his power over the PLA also included several structural changes aimed at increasing the PLA’s capacity to pursue foreign policy interests – like the replacement of “major military regions” with “allied commands” for example. Our discussions with Chinese officials have provided us with a clearer picture of how China is reforming its military to allow for ‘contingencies’ that look a lot like the sorts of interventions we’re used to seeing from superpowers intent of preserving their national interests. We have closely followed the development of China’s ‘secret’ military base in Badakhshan, Afghanistan and tried to establish independent information on its scale and purpose.

The key relationship that is discussed in political risk circles regarding OBOR is the Sino-Russian relationship. Recent co-operation between China and Russia on a number of strategic issues such as oil, military exercises and sanctions overshadow the real geo-political risk that will emerge as China strikes further into Central Asia.

The Russia-China relationship is historically unstable and there is lingering mistrust on both sides. In the short term, both Russia and China recognize they have much to gain by co-operating on their shared goal of reforming the international political order however both are also acutely aware that Beijing holds the strategic long-term edge in the relationship. So Russia is in a precarious position, Putin has enjoyed his greatest geo-political successes as an opportunist rather than a grand strategic planner, and while he sees the short term strategic advantages of close relations with China, his strongly held worldview that Central Asia should remain part of Russia’s sphere of influence will cause significant medium-term tensions between the two countries.

But while China’s relationship with Russia could pose a number of potential geo-political threats, we believe that the larger OBOR related risks being overlooked are country specific and regional. To conceptualise these risks we are continuing to model how China may respond to specific threats and how these threats might impact on OBOR. Country specific threats might be Islamic terrorism, government collapses, coups, internal land disputes, state sponsored corruption, direct and indirect expropriation or popular uprisings in countries such as Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Djibouti and Myanmar. Regional tensions might include conflicts between countries like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan over water and borders, between India and Pakistan over the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or between Myanmar, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh over refugees, shipping lanes, access to ports and Freedom of Navigation. We look at the probability of these events, the scope and timeframe of events and what impacts they will have on specific and overarching OBOR investments. Over the next three months we will be sharing our findings and outlook with clients in the same way we did in 2016.

In political science, we consider an emerging market to be one where political outcomes mean more than economic outcomes. China’s biggest diplomatic failures have come when Beijing has assumed that the promise of economic riches would outweigh any domestic or political concerns about their investment. If history has taught us anything, it is that economic outcomes often take a back seat to legacy political and security issues that involve national pride and power.

China may not want to involve itself in domestic or regional disputes but in driving OBOR forward, China is on a collision course with the same fate that has met history’s other reluctant superpowers and they too will learn ‘it’s tough at the top’.